10 typical mistakes navigators keep making

#1 IGNORE CONTOUR INTERVALS.

Seems like an obvious thing, but quite often we take a map and focus on route planning without paying enough attention to the legend of the map. Mountainous areas might have 20 (even 50) meter contour intervals which makes it a whole different story, as steep climbing as well as steep descending slows you down dramatically and ultimately leads to a different route choice strategy.

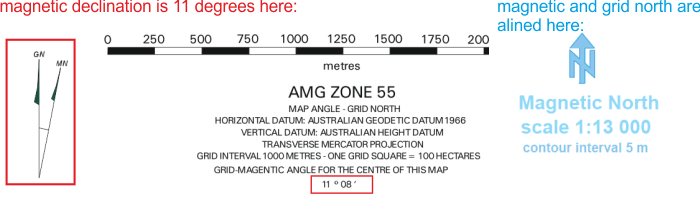

#2 FORGETTING MAGNETIC DECLINATION.

How far are you going to be from where you were aiming at if your direction is 10-20-30 degrees off what you thought you were following? Lets just say that for a distance of about 1 km with 10 degrees declination you will be off approximately 200 meters. If we’re talking about 30 degrees it’s already 350 meters or so.

You’re convinced magnetic declination is important, right? In theory magnetic declination is the difference between true north and magnetic north. Magnetic north is the north where your compass is pointing, true north is geographical north. In practice all you need to know is where grid lines on your map are pointing to, magnetic or true north. Good news here, it’s quite obvious if you know that generally orienteering maps are aligned to magnetic north, topographical are aligned to the geographical north. Bottom of the map (a legend) usually has a picture indicating what magnetic declination is for the map or a symbol indicating that map is orientated to the magnetic north. The easiest way to deal with a map aligned to true north is to draw magnetic north lines or bear in mind there is an angle and account for it each time you take a bearing.

#3 Take a bearing from uncertain points.

This one is a classic. No matter how experienced you are, we all still tend to do it. The rule is that you cannot arrive at a certain point if your origin is uncertain. When you’re planning to go off road and would not have many points along the way to help you find out where you are you cannot start from nowhere, you need an obvious point (like an intersection, dam or knoll).

#4 Do not use ‘attack points’.

It related to the previous one partly. “Attack points” are certain points on the map to be used to position yourself on the map. Basically, it is your strategy of getting to the checkpoint. It could be navigating to a summit (or other obvious feature) first before taking a bearing to your checkpoint. The strategy should be worked out prior to the start if possible. If not,this is what you should be thinking about when you have ‘free’ from navigation periods (eg. time running along the road, etc).

#5 Do not use ‘catching points’.

Catching points are the objects on the map you use to “catch” yourself if you’re off the course (or gone too far). It is always better to have a risk management plan ready, no matter what you do. Here is your risk management plan. It may be a creek, road, ridge.

#6 Fail in distance estimation.

Going through thick vegetation, we tend to underestimate distance, while running on a smooth road it could be the opposite. Even visual estimation can be difficult for some people. Practice during your training runs using a GPS, it could teach you how much it takes you to run/walk certain distances on certain surfaces.

#7 Running faster than you can think.

You cannot go 100% of your speed and navigate at the same time unless you’re a National orienteering team member. There is a fine line between going too hard and hard enough. From our experience if you jump over your anaerobic barrier for a few times during more than a 3 hour event you most likely will get quite badly lost at some stage. It is worth slowing down a little, to give yourself time to figure out where you are. Make sure your team mates understand this too!

#8 Rely on the map too much.

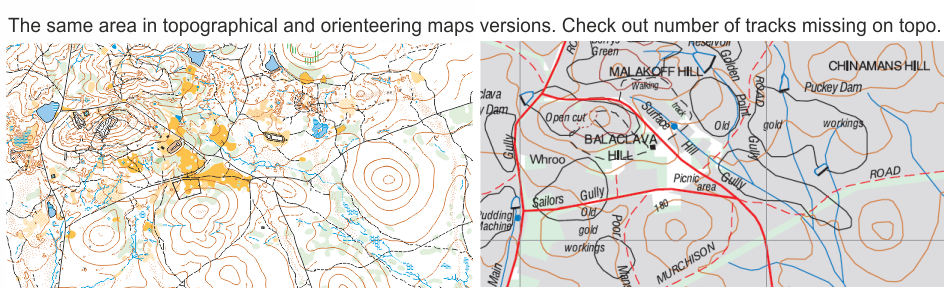

Maps used for rogaines and adventure races are quite likely not orienteering maps. Quite often roads and built up areas shown on the maps may not be up-to–date. Never trust roads (but especially tracks), trust only contour lines!

#9 Trust your ‘inner feeling’ rather than a compass.

How many times you had this feeling of going THAT way instead of following your compass and then failed? After a few hours of racing we can lose our feeling of direction quite often. Bear it in mind and trust your compass.

#10 Follow someone else without navigating yourself.

This might be a strategy for some teams. But the risks are high. You may find out those guys are not quite sure where they were going too? Or you could fall behind and have no idea exactly where you are. In other words, you’re dead lost. Crowds can affect your better judgement. I There is nothing wrong with following someone (unless it is not against the rules of the event) but make sure it is exactly the same way you where going to go.